It is notoriously difficult to reconstruct the biographies of lowly people in the past. But there are lives, testimonies, and obituaries of early plebeian Methodists in denominational magazines and other publications. One obituary of considerable interest is that of Samuel Barber (1783-1828), published in The Primitive Methodist Magazine in 1829. For Barber was not only an early Primitive Methodist lay preacher but also a man of mixed race.

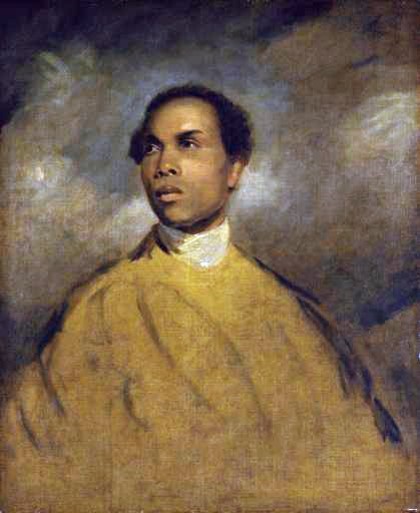

Samuel Barber was born in 1783, in London, the son of Francis Barber, the black, formerly enslaved servant of Dr Samuel Johnson, and his English wife, Elizabeth. Francis was Johnson’s residuary legatee, and the Barber family, after its benefactor’s death in 1784, moved to Lichfield, Johnson’s home town. There Samuel attended a boarding school and, in c.1797, entered the service of a Burslem surgeon, Gregory Hickman. Later, he entered the employ of the Burslem potter Enoch Wood (who had produced the most famous bust of John Wesley). Barber became a potter’s printer, preparing the designs for transfer on to the wares; he came to work frequently fourteen or sixteen hours a day in the potteries.

While Hickman’s servant, Barber was, he afterwards claimed, ‘as proud a fop as ever lived’. He seemingly went ‘as far in dress and ornament as his circumstances would admit’, and was, too, ‘much given to dancing, music, and gay company’. These details are derived from the obituary, written by the Primitive Methodist preacher John Smith. Smith knew Barber personally in Staffordshire in the 1820s, and hence could write authoritatively; but it must be stressed that the memoir is also formulaic and heavily didactic, and potentially distortive.

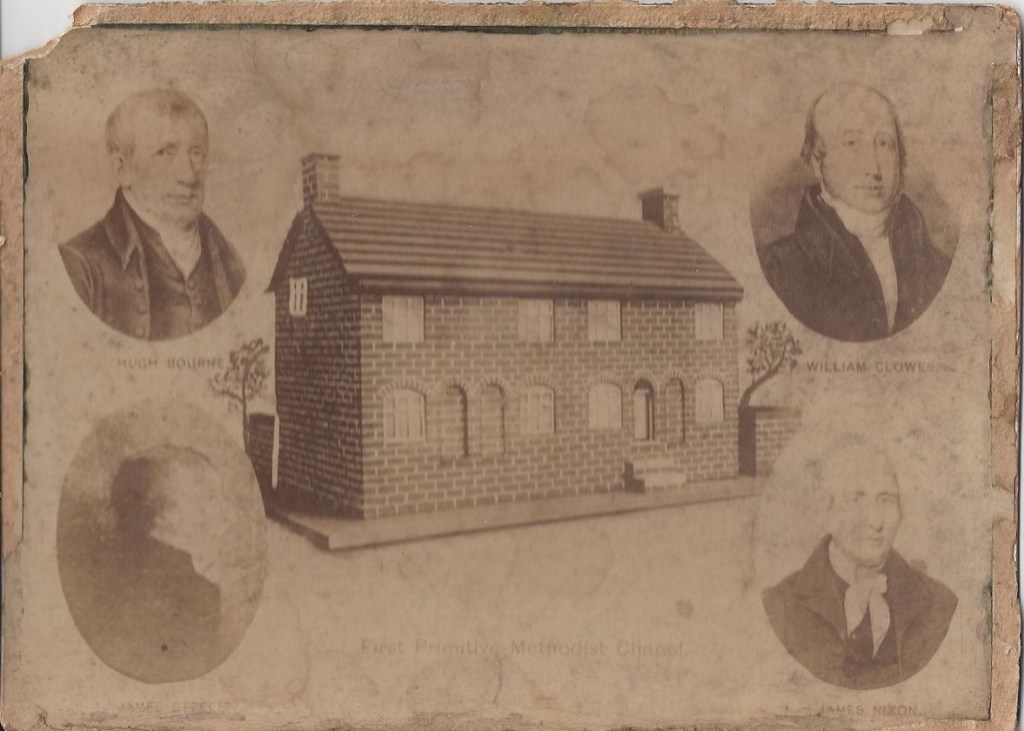

In 1805 or 1806, Barber attended a Methodist assembly at Burslem, and was hugely moved by the preacher. Beset by agonies of conscience and fears of hell, the ‘gay young man now appeared like a condemned criminal’. Then, one Sunday, he knelt in the snow, crying ‘“God be merciful to me, a sinner”’; whereupon, the ‘load of guilt and misery was removed, [and] the speaking blood of Jesus proclaimed God reconciled’: ‘Heaven was within him.’ For Barber, moreover, his residence in the Potteries doubtless appeared providential. In 1810, Hugh Bourne and William Clowes established the Primitive Methodist Connexion, and, the next year, its initial general meeting was held, and its first chapel built, at Tunstall, where Barber, it seems, now lived. Barber quickly joined the Primitive Methodists.

Feeling ‘a growing deadness to the world’, Barber yearned for a deepening sense of God’s presence for himself. For others, he desperately wanted to secure ‘the welfare of immortal souls’. Humans, he wrote, might ‘be saved, God is just, and the justifier of all that believe in him’. Christ died for sinners. But Barber also emphasized the torments of hell, ‘everlasting burning […] with devils and damned spirits’. Life was short, he told his hearers, and they should remember ‘the unbounded goodness of God’, His ‘inflexible justice’, and ‘the durability of Hell torments’.

Barber was a local preacher from 1809; when he died, he was the eleventh most senior of fifty-five preachers on the Primitive Methodists’ Tunstall circuit. As a preacher, ‘his talents’, Smith thought, ‘were not of the first order’. Nevertheless, his sermons could be powerful and, to those with troubled consciences, biting and terrifying; his uncompromising theology was easily intelligible to plebeian Primitive Methodist hearers. On some Sundays, Barber went fifteen or twenty miles in order to preach, returning the same day. The 1815 Tunstall circuit plan illustrates his commitment: ‘12th November 10am Norton 2pm Dunwood […] 17th December 10am Wrinehill 2pm Englesea Brook’. As a repentant sinner, he was probably greatly compelling.

Barber’s other evangelizing endeavours amply compensated for any deficiencies in his preaching. After his conversion, he ‘became useful’ in the Burslem Sunday School. He instructed the poor in the workhouse weekly. He was the secretary of the Tunstall Religious Tract Visiting Society, which, in the words of a handbill, aimed to distribute ‘Testaments, Sermons, and Religious Tracts’ to ‘the thoughtless or ignorant poor’ in remote places. He himself distributed tracts, travelling many miles to the neighbourhood’s cottages, and visiting the poor. ‘Several places, where there are now good societies,’ Smith noted, ‘were opened by him.’ When opportunities presented themselves, he evangelized among ‘shop-mates, neighbours, or strangers’, since souls ‘were alike valuable to him’.

How important for Barber was his part-African ancestry? His skin was noticeably dark, and, locally, he was known as ‘Black Sam’. Long after his death, Hickman’s daughter called him ‘a mulatto servant’; another, very elderly lady used ‘negro servant’. His son, Isaac, had ‘woolly hair’. Before his conversion, Barber was certainly troubled by his lineage. The Devil ‘suggested that there was no mercy for him, because he was of African extraction, and was of the coloured tribe’; and Barber thought ‘that his soul was deeper dyed than his body’. Such concerns linking race and sinfulness perhaps persisted. If so, they may partly explain his strictness with, and beating of, his children, considered over-severe by some friends. When he died, The Liverpool Mercury noted he was the son of Johnson’s ‘faithful black servant’.

Barber died in 1828, convinced that he was saved. Of course, it would be possible to write a hostile account using the information provided by Smith: an account depicting Barber as a religious fanatic, a psychological bully, a monomaniac (and monumental) bore. Readers of this blog may do that for themselves -– or perhaps already have. Yet that risks intruding anachronistic value-judgments, value-judgments spawned in an increasingly secular-minded age. Smith’s obituary has the virtue of presenting the life while espousing Barber’s own world-view, and stressing the beliefs and convictions which, for Barber, gave his life (on Earth) purpose.

Dr Colin Haydon has published widely on the history of religion in England from c1660 to c1820, including Anti-Catholicism in Eighteenth-Century England c.1714-80 (1994) and John Henry Williams (1747-1829): ‘Political Clergyman’ (2007). He delivered the annual John Wesley Lecture at Oxford in 2019

2 replies on “Black History Month – Samuel Barber (1783-1828)”

Thank you for sharing this information.

LikeLike

My direct 3× great grandfather is a great inspiration to me. He lived in my home city of Stoke-on-Trent and all his children and further descendants were born in Burslem, including me.

He was a born-again believer and ‘on fire’ for Jesus! Since discovering this ‘black heritage’ of mine, I have been encouraged beyond words. Today we need preachers like him to take the gospel into our nation and see souls saved.

LikeLike