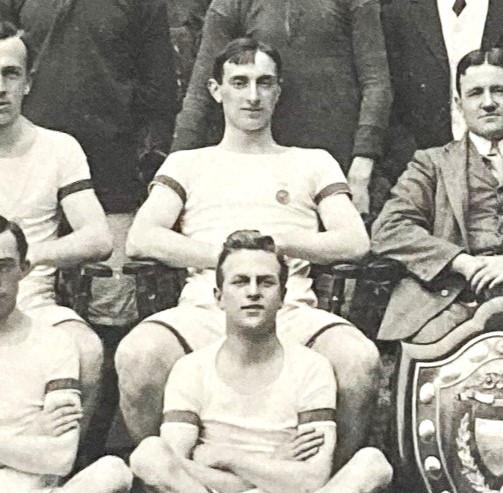

(D. S. Bell at Westminster Training College, 1909-11)

Donald Simpson Bell (1890-1916) was born into a family of Wesleyan Methodists in the North Yorkshire spa town of Harrogate on 3 December 1890. The youngest son of Smith and Annie Bell, he attended St. Peter’s Church of England Primary School as a child before continuing his education at Harrogate Grammar School.

In 1909, Bell left Yorkshire and moved to London to train as a teacher at Westminster College. A naturally gifted athlete, he excelled at many sports and quickly forged a fine reputation for himself in college sporting circles. He was an accomplished cricketer, a lightning quick sprinter and a talented hockey player. Standing over six-feet tall and powerfully built, he was also competitive in the swimming pool and fearsome on the rugby field.

15 May 1911 (top right) Westminster Training College Fifth Inter-Year Athletics Sports programme, 15 February 1910 (middle) programme, 14 February 1911 (below)

Football was his first love, however, and Bell had already impressed in Yorkshire’s amateur leagues before emerging as one of the stand-out players in the Westminster XI. His talents were also recognised by Southern League side Crystal Palace who gave him the opportunity to turn out for them as an amateur while he studied in the capital.

Bell eventually returned to his native Harrogate in 1911 to take up a teaching role at Starbeck School. Nevertheless, football continued to occupy a significant part of his life and he had brief spells with Newcastle United reserves and Bishop Auckland before helping Mirfield United retain the West Riding Junior Cup in 1912.

Bell’s growing reputation soon caught the attention of Bradford Park Avenue and the second division club were eventually persuaded to offer him his first professional contract, which he signed in October 1912 in order to supplement his modest teaching salary.

After establishing himself in the second string, Bell made his Football League debut against Wolverhampton Wanderers at the end of the 1912/13 season and would go onto play a further four league games the following season as Avenue secured promotion to the English top flight. Although his first team appearances were limited, Bell was a regular fixture in the reserve side and he impressed sufficiently to suggest he had a promising future ahead of him.

Unfortunately, his burgeoning football career was cut short soon after the outbreak of the First World War when he asked Avenue to release him from his contract so he could answer Lord Kitchener’s call to arms. This was duly agreed and Bell enlisted as a private in the 9th West Yorkshire Regiment in November 1914.

Bell was a natural soldier and he was soon persuaded to apply for a temporary commission after a chance meeting with former Harrogate Grammar school friend Archie White, who was then serving as a Lieutenant with the 6th Yorkshire Regiment, also known as the Green Howards. Bell’s application was subsequently approved and, after completing office training, he eventually embarked for France where he joined the 9th Green Howards as a second-lieutenant in December 1915.

Bell’s first taste of life in trenches came in a relatively quiet sector of the line near Armentieres, however, his battalion eventually moved south ahead of the British offensive on the Somme in the summer of 1916. As part of 69th Brigade, 23rd Division, the battalion were held in reserve on the bloody opening day of battle but they were soon thrown into the maelstrom when they were ordered to assault a German position called Horseshoe Trench on 5 July.

Unfortunately, the attack ran into difficulties almost immediately as the exposed Yorkshiremen were raked by withering enemy machine-gun fire soon after clambering from their trenches and quickly began taking losses. At this critical moment, 2/Lt Bell took decisive action and set off towards the machine-gun along a communication trench with two men from his bombing party, Corporal Colwill and Private Batey, following quickly behind. When the trio had closed to within twenty yards of the gun, they suddenly leapt out of cover and made an audacious charge across the open, straight towards the startled enemy.

Bell first managed to kill the soldier firing the gun with his revolver before launching a well-placed Mills bomb that succeeded in destroying both the gun and the remaining members of the gun team. The three men then proceeded to clear out a number of dugouts with the aid of further Mills bombs. With the deadly threat on their flank removed, the Green Howards surged across no-man’s land and down into the German trenches, where they were soon able to secure their objectives.

Bell’s quick-thinking and gallantry proved critical to the eventual success of the British attack on Horseshoe Trench that day and undoubtedly saved the lives of many soldiers. Nevertheless, Bell was a reluctant hero and he was characteristically modest about the incident when he wrote to his mother soon after, telling her dismissively: ‘I must confess that it was the biggest fluke alive and I did nothing… I chucked the bomb and it did the trick.’

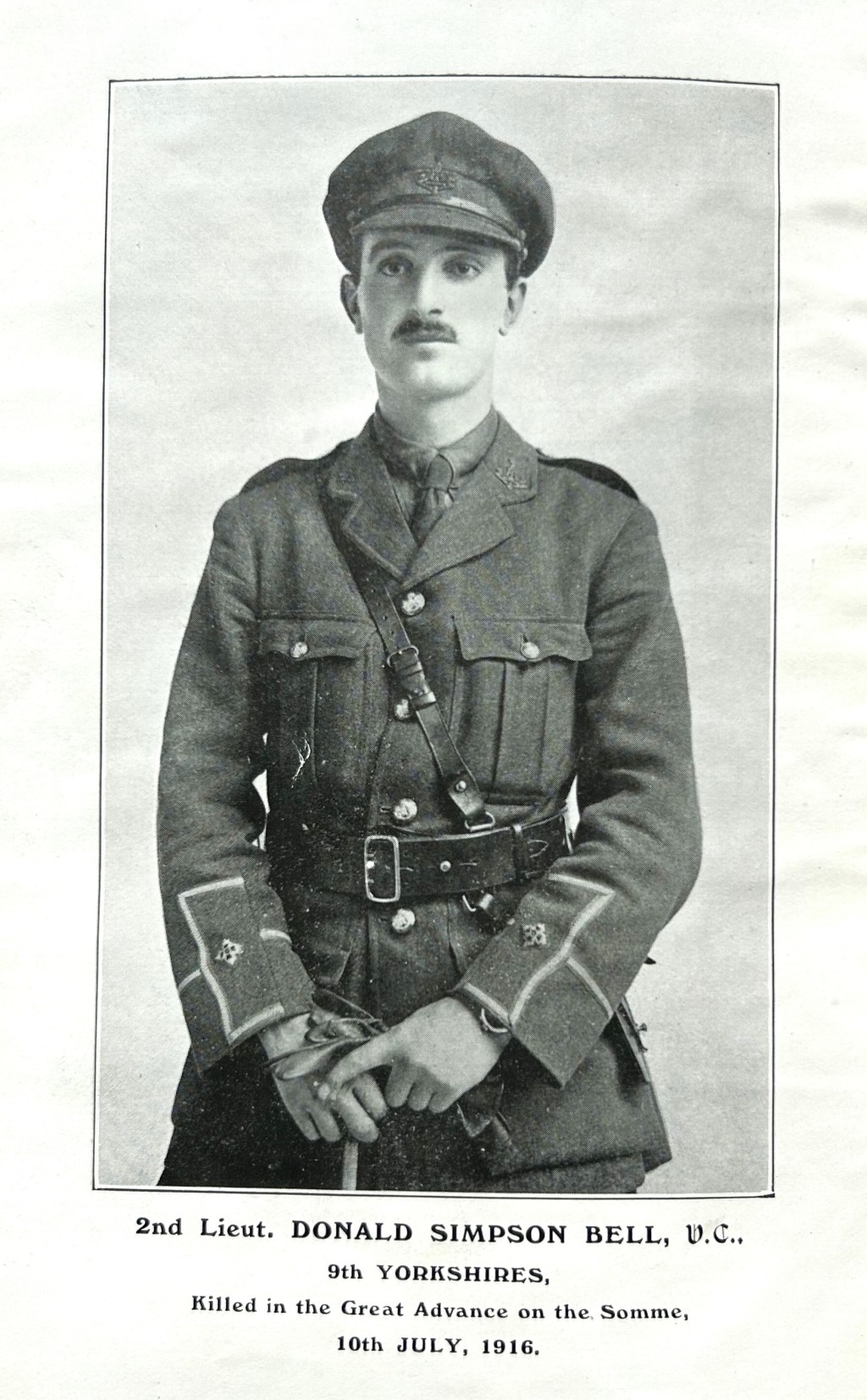

Tragically, that letter would prove to be the final correspondence between the pair. Five days after the attack on Horseshoe Trench, Bell was cut down leading a similarly dramatic bombing attack against the enemy during the fight to capture Contalmaison. He was twenty-five-years-old and left a widow, Rhoda, who he only married four weeks earlier during a short period of leave. After his death, the popular subaltern was buried close to where he had fallen at the southeastern end of the village and a wooden cross later placed on his grave. A nearby position was also named Bell’s Redoubt in his honour.

News of Bell’s death prompted an enormous outpouring of grief at home and a flurry of emotional tributes soon followed. Among them was one published in the Westminster Training College Monthly War Bulletin which said of their former student:

At college, Bell had been Captain of Athletics, and a member of the first eleven at cricket, Association football, and hockey. He had also represented the College at swimming and Rugby football, and was in fact one of the best all-round athletes that Westminster has ever produced .[i]

There were also tributes from his battalion, including one from his commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Holmes, who told Bell’s parents that their son was ‘a great loss to the Battalion and also to me personally, and I consider him one of the finest officers I have ever seen’[ii]

Another officer said Bell ‘knew no fear’ and added ‘he had the courage of a lion, and always seemed to be on the lookout for ways and means of making things easier for his comrades.’[iii]

Archie White, meanwhile, who remarkably would also be awarded the Victoria Cross for deeds at Stuff Trench less than three months after Bell’s death, wrote of his old school friend: ‘Probably no one else on the front could have done what he did… He was a magnificent soldier.’[iv]

On 9 September 1916, the London Gazette announced that Bell had been awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross for his actions at Horseshoe Trench on 5 July. He was the first and only English professional footballer to receive his country’s highest decoration for gallantry during the war. The citation read:

For most conspicuous bravery. During an attack a very heavy enfilade fire was opened on the attacking company by a hostile machine gun. 2nd Lt. Bell immediately, and on his own initiative, crept up a communication trench and then, followed by Corpl. Colwill and Pte. Batey, rushed across the open under very heavy fire and attacked the machine gun, shooting the firer with his revolver, and ‘destroying gun and personnel with bombs. This very brave act saved many lives and ensured the success of the attack. Five days later this gallant officer lost his life performing a very similar act of bravery.[v]

On 13 December 1916, Rhoda Bell travelled to Buckingham Palace to receive her late husband’s award from King George V. She was accompanied on her visit to London by his sister, Minnie, and the pair were photographed outside the palace gates following the ceremony. Corporal Colwill and Private Batey, meanwhile, later received the Distinguished Conduct Medal in recognition of their bravery on 5 July. Unlike Bell, both men survived the conflict and lived into old age.

After the War, Bell’s body was moved from its original resting place and reburied at Gordon Dump Cemetery in the valley below the village of La Boisselle. Perhaps fittingly, the gallant young officer now lies just a few hundred yards from the site of his heroic action at Horseshoe Trench.

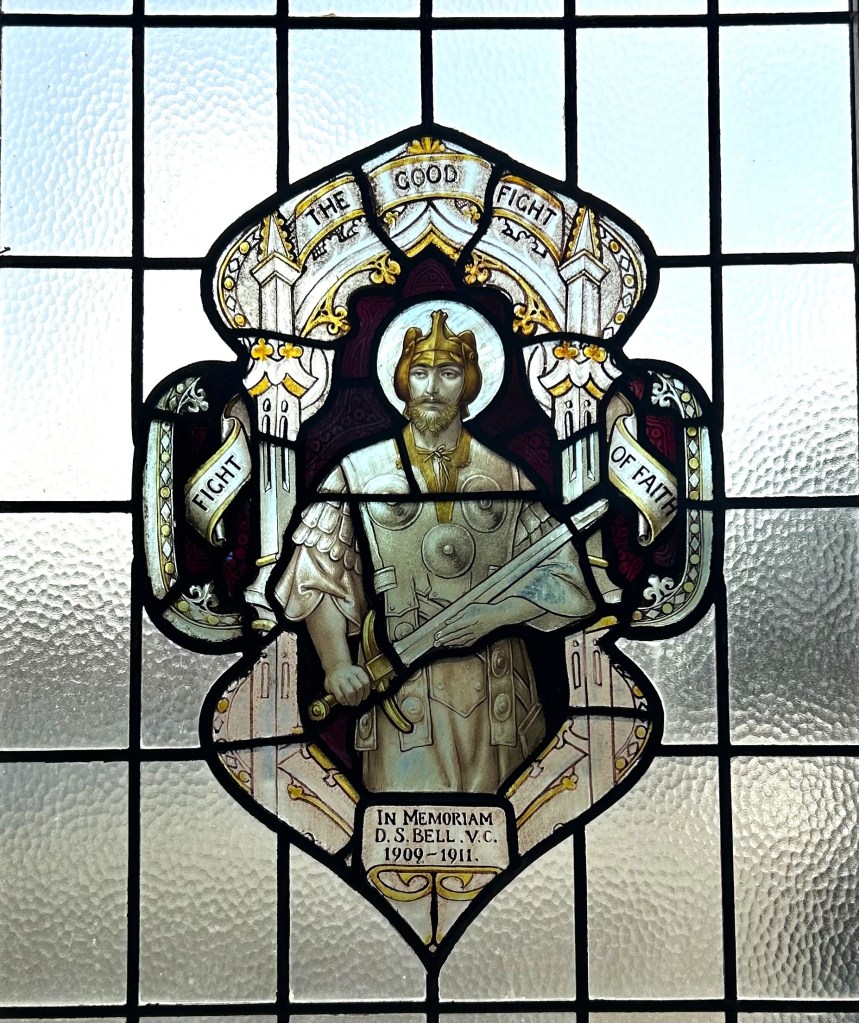

Bell is commemorated on a number of memorials, including one at the Wesleyan Chapel in Harrogate and others at St. Peter’s Church of England Primary School and Harrogate Grammar School. There is also a beautiful stained glass window in the chapel at Oxford Brookes University at Harcourt Hill that honours the former Westminsterian.

In 2000, a memorial sponsored by the Players Football Association (PFA) and the Friends of the Green Howards Museum was erected on the site of Bell’s Redoubt to commemorate the gallant young officer. Almost one decade later, the PFA also bought his Victoria Cross and campaign medals at auction and they are now on display at the National Football Museum in Manchester.

Iain McMullen

Images from the Westminster College Archives provided by OCMCH staff, many of which can be viewed online through our Digital Collections page here

[i] F. C. Pritchard, The Story of Westminster College, 1851-1951, p. 125

[ii] Letter to Smith Bell. Bell Family Archive.

[iii] Harrogate Herald (9 May 1917)

[iv] R. Leake A Breed Apart, p. 84

[v] The London Gazette (9 September 1916)

Leave a comment