Much progress has been made in the Francis L. Bartels Collection since last October’s post. My contribution was discussed as a potential task back in January 2020 as I was about to embark on a placement module in my second year as an Undergraduate, though in the end I worked on a different project – until the placement was cut short. When the first lockdown hit, I still had five weeks left with the Centre. Though I was not penalised in the marking of the module, I certainly felt I had left something unfinished, and yearned to return to the archive to carry out further work. After graduating this July, I reached out to Tom Dobson, to inquire about the possibility of a further voluntary placement over the summer. Throughout August, I listed approximately 600 individual items for the collection.

Dr Peter Forsaith has already discussed Dr Bartels’s biographical details in a previous post at length, for me to repeat them here would be superfluous – I shall instead discuss the impression of Bartels that listing his personal papers has left me.

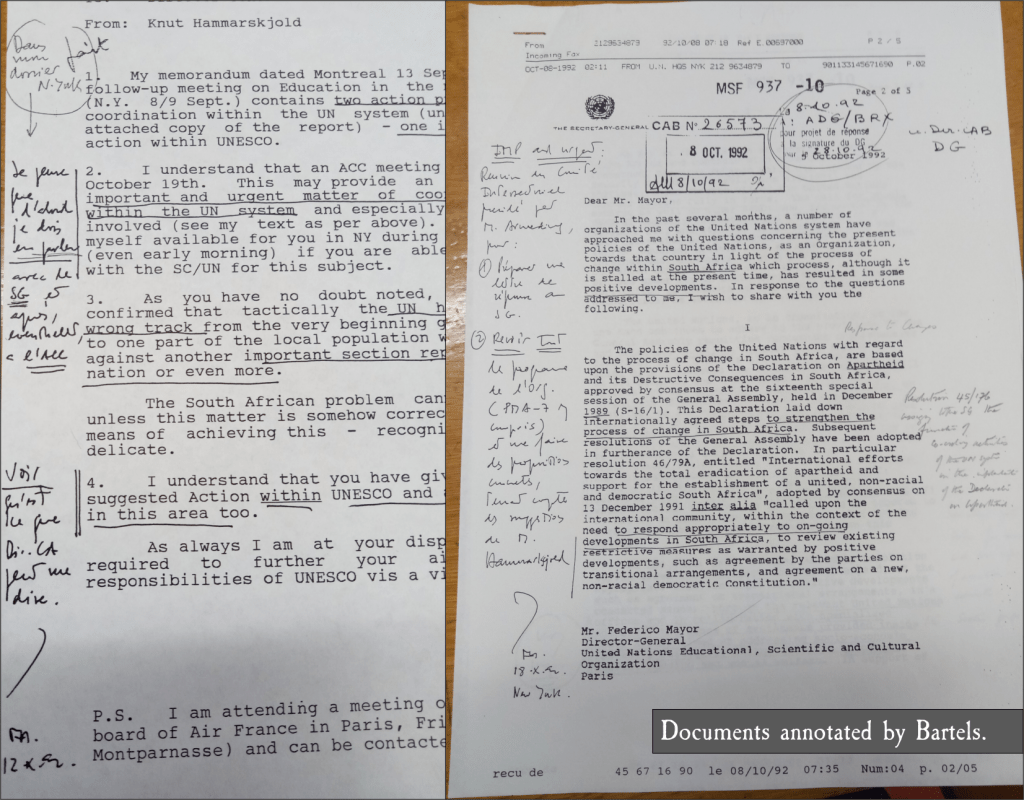

An incredibly diligent man with a profound attention to detail, many of the documents within the collection are extensively annotated front and back.

Bartels would pass on notes regarding speeches and reports regularly, suggesting changes in phrasing here and there, or provide unrestrained critique if the document in question did not meet his exacting standards.

Peering into Dr Bartels’s collection of newspaper clippings, we may discover a different side of the man. Of the pages he’d kept from The Listener, for example, the majority are printed sermons by Gerald Priestland,[1] indicating an enduring interest in questions of religion and spirituality.

This notion is further reinforced by Bartels’s membership of the Society for African Church History.

The existence of the collection itself also betrays a lot about Bartels. While the original organisation of the collection may have suffered as a result of storage and transport before it made its way to the OCMCH, Bartels clearly had a system in mind as he saved various documents and organised them within it. Correspondence, conference materials, newspaper clippings, and other publications are all collected and labelled in various folders according to their relation to either specific events or broader themes. This is not a collection of all the papers that had been found among Bartels’s effects upon his death, but a system he had evidently been curating throughout his whole life. It is difficult to put into words what it feels like to peer into a life’s work.

Indeed, listing the documents has been more akin to trying to reconstruct a catalogue following the original’s destruction. Dr Forsaith’s ambition is to organise the collection so that were Bartels still alive today, he should still be able to find a specific document in it. This is a worthy goal.

Michael Orsovszki

MA History student at Oxford Brookes

[1] Quaker and BBC religious affairs correspondent between 1977 and 1982

Leave a comment