Alison Butler of the Methodist Heritage Committee reconsiders Freeman’s legacy

In marking the contribution of Thomas Birch Freeman to Methodism’s missionary work, we should surely also recognise those less well-known helpers, whose work ensured Freeman’s success.

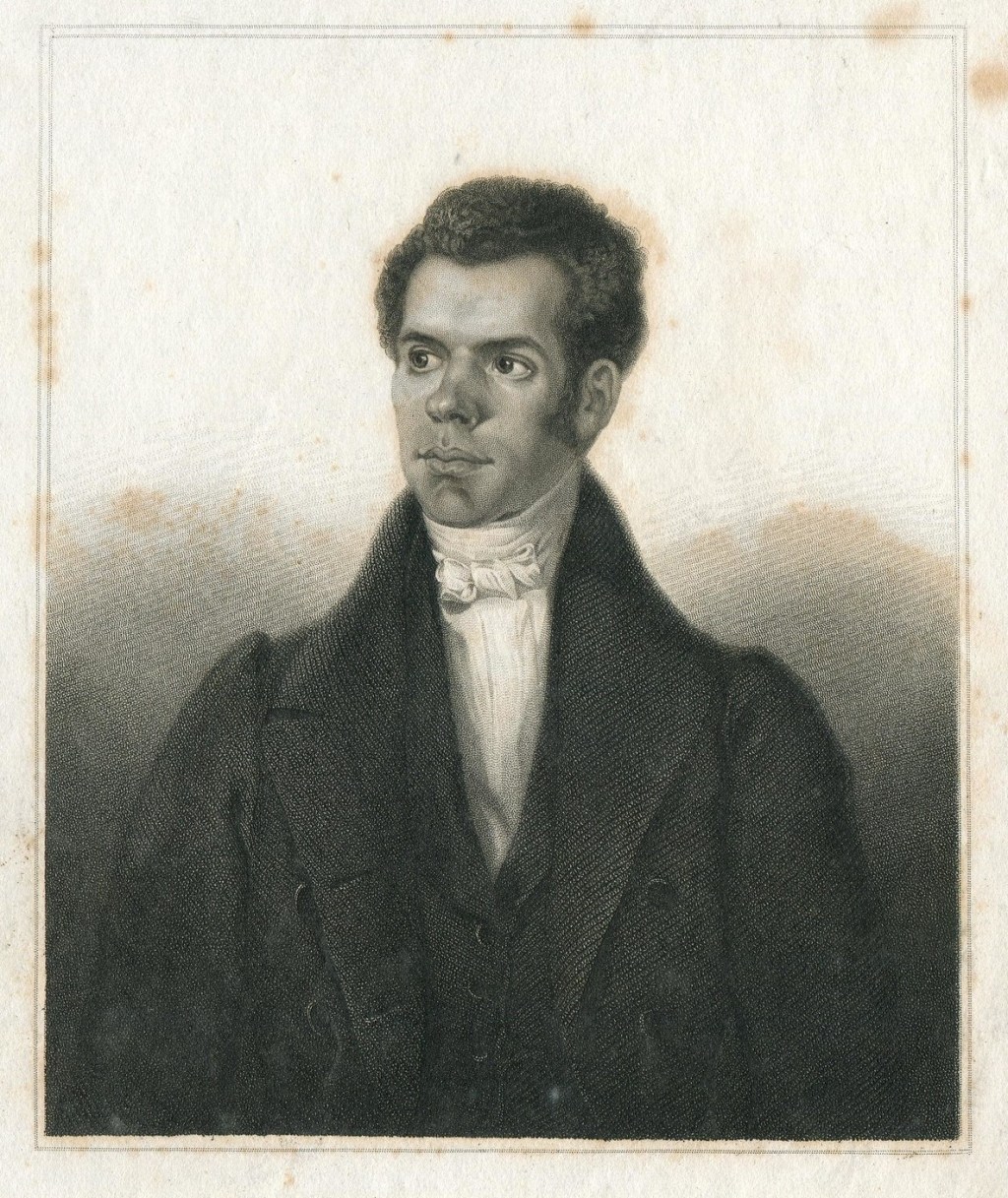

https://flic.kr/p/2edhqLf

Such as they are, the biographical details relating to Freeman are readily available[1] and his story has been told before in Black History Month[2]. His service as a successful and particularly long-lived Wesleyan Methodist missionary in West Africa between 1838 and 1857 and then again from 1878 to 1890 has been recounted in respected biographies and authoritative accounts of the work of Methodist missions[3]. However, even setting aside the more complex issue of the entanglement of British missionary and colonial interests, I am wondering whether a reappraisal of his personal contribution is not now due.

For what is barely explored is the extent to which Freeman’s effectiveness was indebted to the humility, capability and commitment of African Christians, some of whom were witnessing to their faith before Methodist missionaries such as Freeman arrived. These men and women are almost always referred to, in passing, as having been ‘identified’ as suitable workers, or who, in the case of William de Graft, ‘accompanied’ but quite possibly out shone Freeman, on their successful missionary lecture-cum-fundraising tour of Britain in 1840.

That Freeman was able to acknowledge de Graft to be a gifted speaker and preacher has been framed as, and was, enlightened for the time. But it leaves open to question whether, overall, Freeman learned as much from men such as de Graft, as the other way around. Similarly Freeman’s lauded willingness to recommend black Methodists for ordination, side steps the designation of ‘catechist’ initially given to them. (Had they been white, these men would almost certainly have been immediately ordained, but would then have cost the Missionary Society more.)

Freeman is mildly criticised for having been incompetent at keeping control of his expenditure (and resigned from the ministry in 1857 as a result). Less is made of his inability to speak native languages. Most accounts simply refer to his use of (nameless) translators. Since his preaching was, relatively speaking, extremely successful, one wonders what those who saw him speak actually heard. Where is the credit shown to those who were able to translate, on the spot? How did they manage to communicate the essence of Freeman’s style of preaching in a way that led people to faith?

Thankfully Freeman’s botanical interests and expertise are now receiving some dedicated attention[4], although this work is still to be published. Sadly the two enduring passions of Freeman’s life: preaching the word and studying plants have thus far been researched separately. I suspect a more holistic approach will be needed to do him (and others) justice and to understand who Freeman really was, or at least could have been. One wonders how his life might have turned out, had his employer not made him choose between his faith and his work as a plantsman when he was still a young man.

[1] https://dacb.org/stories/ghana/freeman-t/

[2] https://blogs.soas.ac.uk/archives/2019/10/04/black-history-month-2019-thomas-birch-freeman

[3] Thomas Birch Freeman, West African Pioneer by Allen Birtwhistle (The Cargate Press, 1950); Methodists and their Missionary Societies 1760 – 1900 by John Pritchard (Ashgate Methodist Studies, 2013)

[4] Correspondence with and website of Advolly Richmond, garden historian: https://advolly.co.uk/talks.html

For more information about Black History Month at Oxford Brookes University visit, https://www.brookes.ac.uk/staff/human-resources/equality-diversity-and-inclusion/black-history-month/

Leave a comment